American statesman Henry Kissinger famously coined the phrase that Israel has no foreign policy, only domestic policy. This observation has since been updated to suggest that Israel now has neither foreign policy nor domestic policy—only legal policy and sectoral politics.

This observation applies directly to Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu's strategic declaration at an IDF infantry officers' graduation ceremony, where he stated that Israel would "demand" that the Syrian army not move southward from Damascus, and that Israel would protect the Druze in southern Syria.

Netanyahu carefully chose to say Israel would "demand" this rather than "prevent" it—a cautious verbal strategy that avoids firm commitments while drawing red lines.

In such matters, we must distinguish between establishing boundaries and publicly declaring them. Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin and Syrian President Hafez al-Assad once maintained an effective arrangement in Lebanon—an agreed-upon latitudinal line that Syrian forces would not cross southward. This "red line" arrangement worked effectively for many years precisely because neither side publicly acknowledged its existence.

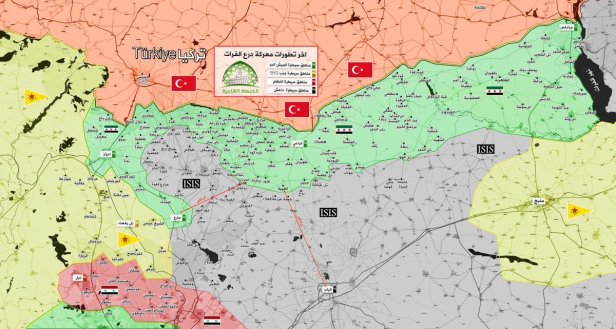

Setting strategic boundaries that leverage the Israeli Air Force's achievements in what was once the "Shiite Crescent" to halt the southward expansion of fundamentalist Islam threatening Israel, the Druze, and Jordan is of crucial strategic importance. The question is whether such decisions should be implemented quietly and effectively behind the scenes, or announced loudly—potentially awakening opposition, organizing resistance, and putting the Druze in a defensive position.

The backlash was immediate. A Druze delegation rushed to Damascus to meet with Abu Muhammad al-Jawlani to disassociate themselves from the Prime Minister's declaration. In Daraa, near the Jordanian border, a large gathering of Arabs and Druze convened to reject the announcement. Jawlani himself warned Jordan against cooperating with Israel on Netanyahu's stated policy, and hurried to Amman to negotiate border arrangements—effectively promising that his government would extend to the southern border with Jordan's consent. Instead of quiet cooperation with Jordan to establish boundaries, Jordan is now coordinating with Jawlani to undermine Israel's strategy.

The greatest danger, however, is that Netanyahu's declarations might provoke Turkey to respond. Currently, Turkey is reluctant to become further entangled in Syria beyond consolidating its gains, but Erdogan might decide not to allow Israel the privilege of controlling southern Syria and could begin rehabilitating the Syrian army.

What would Israel do then? If it were to exercise its air superiority in the former Shiite Crescent region, it wouldn't be like previous strikes against Iranian and former Hezbollah targets, but could risk war with Turkey.

Israel previously had the option to support the Free Syrian Army, the primary force fighting Assad during the civil war, but showed little interest. Now, if Israel is determined to implement Netanyahu's declared policy in Syria, it must urgently reconsider such cooperation.

Netanyahu's declaration has immediate legal implications, as evidenced by his request to postpone his trial due to "important developments"—which he himself created.

With all the secrecy surrounding the confidential report to the judges, one might think we face imminent war with Iran. However, such a conflict would be impractical before normalizing relations with Saudi Arabia, as Iran would retaliate against Saudi Arabia, sending the global energy market into a tailspin.

Attacking Iran requires deploying defensive networks around Saudi oil facilities, which cannot happen without a peace agreement with Saudi Arabia. Yet this peace agreement is unattainable due to Minister Smotrich, who would not agree to gestures toward a Palestinian state—and moreover, the IDF is now transferring operational patterns from Gaza to the West Bank.

This doesn't mean Israel shouldn't forcefully address the dangers posed by Iranian cells in West Bank refugee camps. But when Israeli policy is driven primarily by sectoral and legal considerations, every action or measure must be evaluated according to these criteria.